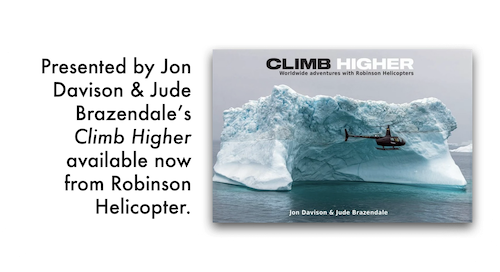

The cover shot from Jon Davison and Jude Brazendale’s 2025 book Climb Higher. (📸 ©2025 Jon Davison | Eye in the Sky Productions)

Getting to Greenland … Finally

A behind the scenes look at one of the twenty-one chapters in our new Robinson Helicopter book Climb Higher by Jon DavisonJude Brazendale. Here we look at the Flying in the Arctic chapter that Jon undertook with Quentin Smith from HQ Aviation in the UK.

By Jon Davison

It’s funny how travel only makes sense months later—after the delays, the chaos, and the what the hell am I doing here moments fade into something that almost resembles adventure. Greenland was like that. Looking back, it’s clear it wasn’t just a trip—it was a test in patience, improvisation, and the sheer stubborn will to see something extraordinary. ― Jon Davison, October 2025

***

The Invitation

Ihad been emailing back and forth with Quentin and Juliette Smith from HQ Aviation in the UK, sorting out dates for a chapter in our new Robinson Helicopter book. Then Juliette casually dropped a line near the end of one email:

Q is departing Sunday 6th July late PM for a Greenland exploration mission with two R66s. Might be a good opportunity to take some shots about what we, at HQ, enjoy doing. (Perhaps meet the explorers in Kulusuk?) I read it twice. Greenland … Two R66s … Exploration mission.

Q is departing Sunday 6th July late PM for a Greenland exploration mission with two R66s. Might be a good opportunity to take some shots about what we, at HQ, enjoy doing. (Perhaps meet the explorers in Kulusuk?) I read it twice. Greenland … Two R66s … Exploration mission.

Well, that took me by surprise. I’d always been curious about Greenland—vast, icy, surreal. And knowing Q’s track record with his epic flights around the world and both poles, I had no doubt this one would be colourful and probably a bit … different. So I fired off a barrage of questions: How do I get there? What will it cost? What do I take? Can we do air-to-air shots? And what exactly are you doing there?

Juliette replied that there’d be two R66s, a team of four—including Q—and maybe I could join them somewhere along the way. Intriguing didn’t even begin to cover it.

The Plan

Flights checked for July 8: Toulouse, Frankfurt, Keflavik, Kulusuk. Cost: €2,523. Expensive, sure—but my photographer brain was already obsessed with the imagery. Icebergs. Glaciers. Arctic light. That was it. Once the seed was planted, there was no turning back.

Jude and I decided I’d go alone—it was too pricey for both of us—as we agreed that we would both meet Q in Denham in the UK on the 8th anyway.

So that was that: pack, go, and hope the world didn’t throw too many curved balls.

Travel Day(s)

Aone hour train to Toulouse. Uber to Blagnac. Then the 06:05 flight to Frankfurt for a three-hour layover until the flight to Keflavik. Then a four-hour layover there until the short hop to Kulusuk on an Air Greenland Dash 8.

It was supposed to be a 12-hour travel day. Supposed to be. Thirty minutes over the Greenland Sea, the cabin pressure went haywire. Everyone started popping ears and looking around nervously before the captain came on:

We have a problem equalising the pressure, so we’re heading back to Keflavik - below 10,000 feet.

Really, Sherlock.

Back to Iceland and a hotel overnight. Try again tomorrow. Next morning, the same bright red Dash 8 was waiting on the tarmac under a foreboding sky. We lined up to board, only to be told: flight cancelled.

Cue the mass eye-roll. Another hotel—this time forty minutes away in Reykjavik, for some reason.

Groundhog Day in Keflavik

July 10th. Another forty-minute taxi back to Keflavik. Another Dash 8—but this time with Iceland Air, not Air Greenland. Spirits cautiously up. Then, just as I was about to board, a message from Q popped up:

We’ve left Kulusuk and are heading to Ilulissat across the icecap, then up through Nuuk. Where are you? I replied:

Damn it! Q, I’m in Keflavik waiting to get to Kulusuk! His next message sealed it:

Hell, if I’d thought about it, we could’ve taken you in the R66 from Keflavik—we had a spare seat. But we’re already halfway to Ilulissat.

Brilliant. Thanks for the heads up, mate.

So, cancel Kulusuk, rebook to Ilulissat—at eye-watering expense. This trip was starting to feel like an endurance test in logistics and luck.

Hello, Greenland

When I finally landed in Ilulissat, the sky was heavy and grey, the air damp. But then I saw it—the view from the hotel restaurant over Disko Bay. Hundreds of cathedral sized icebergs drifting lazily in the water, calved straight from the Jakobshavn Glacier.

Wow, I muttered to no one. Hello, Greenland.

Two days passed. No word from Q. I assumed they were still flying over the icecap somewhere.

So I explored Ilulissat—a sleepy, alpine-like town where every shop sold some version of extreme outdoor gear. Prices were high, spirits higher. I walked the bay at midnight beneath a sky that glowed orange for hours. Icebergs floated and creaked, though it was mostly in silence.

It was surreal—otherworldly. Nothing in my travel history prepared me for it.

Drone Down

On a whim, I decided to try a drone shot—Ilulissat from behind an iceberg looking back to the town and the historic 1700’s Zion’s church. About 300 metres out. Simple.

I took off. Then this message:

You are entering a restricted zone. Shit. Oh no, the airport must be closer than I thought. Then another message:

Landing. No! Please don’t land! Just come back home … you can do it! I fought with the controls, but the screen was filled with white. Ice. Then yellow stairs—a building behind me? Maybe safe?

Nope. More white. Then cut to black.

My brand-new €1,000 Mavic 4 Pro—gone. Straight into the bay or smashed on an iceberg. I stood there, controller limp in my hands, thinking, perfect. Greenland had claimed its first sacrifice.

The Call

Two days later, finally—contact.

Jon, we’re 30 minutes away from Ilimanaq. Can you get there? We have accommodation sorted. I replied:

What? You never told me this! I’ve just booked four nights here in Ilulissat!

What? You never told me this! I’ve just booked four nights here in Ilulissat!

Can you get a boat to Ilimanaq?

No, not today, too late now. An hour later:

Okay, then can you meet us at Ilulissat airport in an hour?

What the hell am I doing, I wondered. So I cancelled the nice warm hotel with the great view and grabbed a cab.

The Meeting

The tiny airport terminal was total chaos. People everywhere, soaked through, speaking different languages. No food, no announcements—just a mass of restless travellers. To add to this, my trusty Timberland boots finally gave up after many years, and the soles started to come away, so my feet were drenched and freezing. I had bought a new pair of socks in town, so I found a heater, set my boots on it, threw the wet socks away, looked for some Super Glue to seal the soles to no avail. Then grabbed a coffee and waited.

Dash 8s came and went. I kept looking outside, no helicopters. I assumed Q and the team knew I was there, and they will come find me and we will head off. I must have nodded off as I was still holding the coffee when I woke, but now it was upside down. But no spilt coffee anywhere, so I must have drank it, but funny I don’t remember doing that.

Then, just outside the windows, two black Robinson R66s, emblazoned with Breitling logos, sitting on the rain-soaked tarmac. I had not heard them land.

A hulking Inuit in a yellow vest guarded the door.

No outside now. You wait for plane to Nuuk.

I am not going to Nuuk, I said. I need to get out there—to the helicopters.

He frowned and shook his head. I found another yellow vest—the ops manager—and explained my situation.

Why you want go outside? Cold and raining.

I know, I am with the helicopter expedition, I need to be out there. Her eyes lit up.

Oh! You are Jon Davison—the famous photographer! We were expecting you. Please, follow me. I blinked.

Really?Had Q sent her a message? She looked past me, scanning the room.

All your equipment, where is it? your lights and assistants? I looked as well, thinking maybe I have lost them? No.

Just me, I said. Everything’s on my back. Camera, laptop, drone—well, was drone—and one yellow travel bag. She sighed, pressed a button, and like magic, the doors opened.

Over The Ice

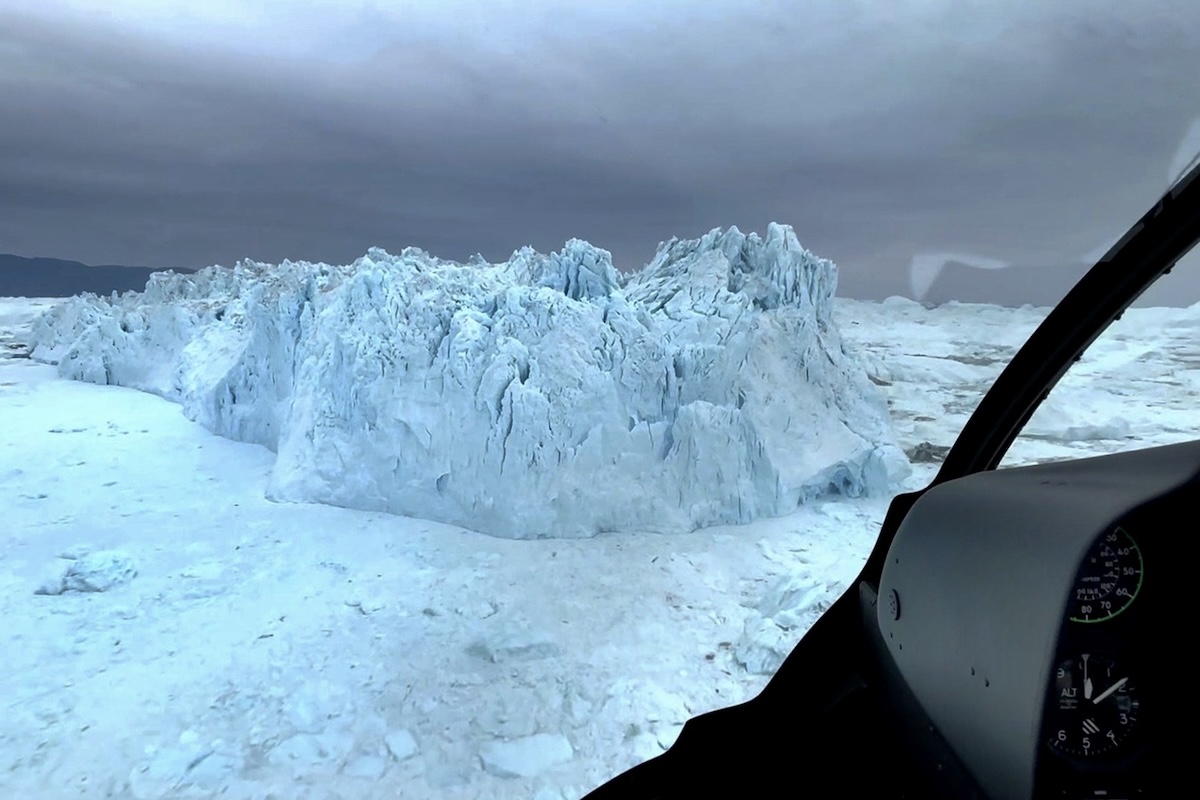

We loaded my gear—what little of it remained—into the helicopter packed with Arctic equipment. Then we lifted off in formation, skimming over Disko Bay and the massive Jakobshavn Isfjord, icebergs gleaming below in ghostly blue. It was raining, misty, cold. The door was off. The wind cut through every layer I had. But the view—unreal. Mountains of ice in every shade of blue, turquoise, and green, streaked with black granite dust.

We flew to the towering face of the glacier—seventy kilometres wide—and then out over the icecap itself.

The immensity of it was overwhelming. I’d seen glaciers before, but nothing like this. It was like flying over the edge of time. On the way back, we did low passes over the bergs. I got the shot—one that would end up on the cover, with Martin flying low past a perfect ice mountain.

He even landed on one, just because he could. That’s how the day went: finding bonuses, it was breathtaking and perfect.

Plans in the Wind

That evening in Ilimanaq, we sampled the local wine while we huddled over maps and weather apps. Plans changed by the hour. Every move depended on a sliver of good weather and a gut feeling. Now I realised it had been this way for all their journey so far.

If we get caught out, Q said, we might have to land on the ice and wait days befoe it clears. So we move when we can.

Then, over dinner:

We’ve decided to head north in the morning—Upernavik, then the B-29 Kee Bird wreck. Jon, you’re welcome to fly with us all the way back to Denham if you like. In fact, I insist.

I hesitated. The thought of crossing the icecap, Iceland, the Faroes, the Hebrides—tempting beyond reason. But as my boots had given up and the soles were hanging loose, my feet perpetually were wet and freezing. Logic finally beat adventure.

I hesitated. The thought of crossing the icecap, Iceland, the Faroes, the Hebrides—tempting beyond reason. But as my boots had given up and the soles were hanging loose, my feet perpetually were wet and freezing. Logic finally beat adventure.

Damn, I said. I’ll have to sit this one out. Q nodded.

Fair enough. I’ll fly you back to Ilulissat in the morning. But we’ll have to drop you in a field a kilometre out—it’s Sunday, and the airport charges a landing fee of a thousand Euros including using the tower.

So the night was spent in the very cool Ilimanaq Lodge with its cool wooden chalets on the edge of the bay, just outside my balcony was a blue green iceberg, just relaxing in the bay. Dinner was at the Egede restaurant, located in the old colonial manager’s house from 1741, and is one of Greenland’s oldest buildings, now fully protected. The house was originally built by Paul Egede, son of the famous missionary Hans Egede, who was the first missionary to come to Greenland.

The End of the Road

Sothe next day Q dropped me in the puddled grass and I trudged the kilometre to the terminal, socks squelching. After I dried my boots out yet again, I found some Super Glue which I hoped would hold it in place until I got back home.

From Ilulissat airport I got a Dash 8 to Nuuk, staying there one night, then an Air Greenland Airbus to Copenhagen with a night there as well. Finally next day I left Copenhagen for Toulouse. Then a taxi all the way to Gaillac, I had missed the train to Cordes and a hotel in Toulouse would have been the same price as a taxi, so …

Jude was at an outdoor concert at the lovely Chateau Saurs so we agreed to meet there. I arrived exhausted, half-dreaming, still hearing the thrum of rotor blades in my head. I stood there, glass of wine in hand, thinking, Did that all really happen?

In the end, that’s travel, isn’t it?

You make plans, the universe laughs, and somehow—through cancellations, lost drones, wet boots, and mad pilots—you end up exactly where you were meant to be.

Greenland wasn’t easy. But the best journeys never are.

Behind the Lens

People often ask what kit I carry on these kinds of trips. Truth is, I travel light—partly by choice, partly by necessity.

On this one, it was just my Nikon D850, one Nikon 28-300mm lens, a MacBook Air laptop, and a Mavic Mini 4 pro drone that now sleeps somewhere beneath an iceberg off Ilulissat.

There’s something liberating about being stripped down to the essentials—no assistants, no lighting crew, no backup plan. It forces you to work with what you have, to adapt to whatever nature throws at you. And Greenland threw everything—fog, rain, bureaucracy, and beauty on a scale I’ve never seen before.

Postscript

The Jakobshavn Glacier—Sermeq Kujalleq in Greenlandic—is one of the fastest-moving glaciers in the world, grinding forward up to sixty metres a day.

If there’s a takeaway, it’s this: the best shots usually come right after you’ve lost your drone, missed your flight, or been dropped in a muddy field with wet feet. That’s when the story—and the photograph—finally align. The expedition was; Martin Duggan, Mark Winterburn and Quentin Smith. 🛩️

***

Here's where you can download JonJude's PDF of this article. You can order Climb Higher by Jon DavisonJude Brazendale from the Robinson Helicopter website. Meanwhile, if you have any thoughts or questions on this story, the authors would love to hear from you. Click or tap any photo in this article for a high-resolution version along with a caption, if available. For much more of Jon's outstanding work spanning many exciting projects over many years, take a look at his Eye in the Sky Productions website.

Q is departing Sunday 6th July late PM for a Greenland exploration mission with two R66s. Might be a good opportunity to take some shots about what we, at HQ, enjoy doing. (Perhaps meet the explorers in Kulusuk?) I read it twice. Greenland … Two R66s … Exploration mission.

Q is departing Sunday 6th July late PM for a Greenland exploration mission with two R66s. Might be a good opportunity to take some shots about what we, at HQ, enjoy doing. (Perhaps meet the explorers in Kulusuk?) I read it twice. Greenland … Two R66s … Exploration mission.

I hesitated. The thought of crossing the icecap, Iceland, the Faroes, the Hebrides—tempting beyond reason. But as my boots had given up and the soles were hanging loose, my feet perpetually were wet and freezing. Logic finally beat adventure.

I hesitated. The thought of crossing the icecap, Iceland, the Faroes, the Hebrides—tempting beyond reason. But as my boots had given up and the soles were hanging loose, my feet perpetually were wet and freezing. Logic finally beat adventure.